Drilling back into the fossil record of life at WBGS, it’s the callousness I recall most sharply. The school operated in an authoritarian framework designed to suppress individualism and encourage conformity. The duty of the staff was to reinforce the values that had been imposed on them in childhood. They saw no reason to interest themselves in their charges as individuals beyond their potential to translate into success in the sporting arena or Oxbridge Entrance. We now live in a culture where grief and bereavement have been developed into art forms but I remember a morning registration where the form tutor announced something along these lines, “Broadhurst is absent today. His parents were killed in a car accident but I don’t want him to receive any special treatment when he returns on Monday.” And when the newly-orphaned Broadhurst duly returned it was “Broadhurst, where’s your absence note?” “B-but Sir, my....” “I know all about that Broadhurst but I must have a note, see to it, won’t you.” That stupendous lack of concern for the welfare of others was regarded as ideal preparation for a lifetime of commuting to the City of London and a career in investment banking.

The centre of intellectual life was located somewhere between the rugby scrum and the parade ground where members of the cadet corps were prepared for the task of inheriting the earth. The parameters of the rugby scrum were directly descended from medieval visions of the Last Judgement – semi-naked souls in torment dispatched into Hell, thrashing in terminal despair. The notion that one should aspire to excellence in this brutal epic of extreme discomfort and human suffering seemed preposterous to me. Every Tuesday (?), a regiment of miniaturised soldiers and airmen would occupy the school and impress the civilian population with the splendour of their uniforms and the sound of their boots in the corridors. Some of the staff, as I recall, would shake the mothballs out of their wartime uniforms and wear them to school. As one of a tiny minority to decline the chance to become one of Dame Fuller’s paramilitaries, what they got up to was largely a mystery. They had an ancient army surplus truck that they fiddled around with. Their weekly after-hours sessions included much polishing and assembly and disassembly of firearms as well as training in the art of barking unintelligibly at the lower orders which came in useful in adult life when buying a season ticket at the local station. If the object of the exercise was the cultivation of belligerence and an indifference to the feelings of others it must be counted a resounding success. For the disinterested observer the challenge was to maintain composure when confronted with the spectacle of these diminutive warriors out in the wider world on buses and trains – the fun to be had from jeering at their pretensions had to be balanced against their propensity for casual violence when provoked. All three services were represented in the Merchant Taylors’ School cadet corps – those dressed as boy-sailors looked especially incongruous sauntering amidships at HMS Moor Park.

In retrospect it’s difficult not to be impressed by the diligence with which any sense of the joy of learning or intellectual discovery was eliminated from the business of education. The teaching style was relentlessly bombastic, information was delivered in bursts of rapid fire with a regime of testing to speedily identify failures. Classroom interaction was limited to periods of interrogation on lesson content with caustic insults for the hapless inattentive – discussion and debate almost never took place. I always admired the fortunate few among us who could give every appearance of being consumed with apathy yet answer to perfection any question that was put to them. Failure to comprehend was entirely the fault of the pupil – anyone naive enough to ask for further clarification would have their inadequacies drawn to public attention without sparing their feelings.

Seniority was everything and served to perpetuate the culture of bullying. Only newly arrived 1st. years had nobody to look down on, sneer at or intimidate – each cohort in turn would prey on those below with a ferocity intensified by their own experience of having been on the receiving end. Sixth formers served as prefects – they had their own blokey common room to which miscreants could be required to report to be shown the error of their ways. Prefects had the power to issue detentions of up to 30 minutes on a Friday after school. A repeat offender careless enough to get two prefect’s detentions would additionally qualify for an hour of Saturday morning school detention. School detention lasted for 3 hours – anyone exceeding that would be rewarded with a trip to the Headmaster’s study where they would be caned for their troubles. It was not unusual for form teachers, anxious to incentivise good conduct, to double any detention earned by one of those in their care and punishments could escalate to an alarming extent.

Only once did I stumble into this vortex of chastisement. The initial detention was for late homework which was then doubled to 2 hours by my form teacher. Arriving early on the Saturday morning, I went to my form room to find some books and was apprehended by another member of staff with nothing better to do, who construed my action as a further offence against school rules (failure to obtain prior permission) and doubled my 2 hours into 4. I was now in line for an appointment with the Headmaster (and his cane) and having served 3 of my 4 hours it was entirely possible that my form teacher, for my own good, might double the additional 2 hour detention into another 4 raising the prospect of a lifetime at school with alternating detentions and canings without ever committing another offence. Happily this dismal prospect was not realised and a combination of my own omerta, some incomplete paperwork and the benign workings of fate spared me.

one of the few surviving images of H Lister in action

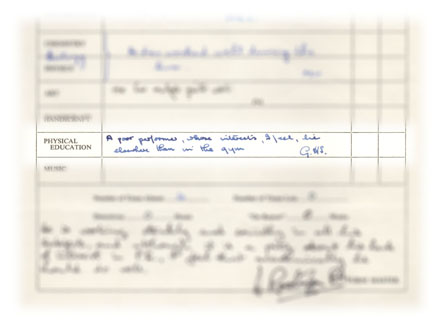

Of all the petty misanthropists who earned a comfortable living tyrannising schoolboys, one stood out – Herbert Lister, Deputy Headmaster, teacher of English and incontinent administrator of corporal punishment. He led by example. His ferocious ability to spot the tiniest infraction of school rules was legendary and when the need arose he could invent a school rule in an instant and make an offender of anyone who aroused his displeasure. Imposing order on the unruly and ignorant was his duty and his relish for the task an inspiration to his colleagues. When he entered a classroom his quivering moustache would arrive a micro-second before the rest of him – the room would be swept for incipient signs of anarchy or subversion. As Chris has memorably described, the first word to be barked at the assembled gathering would be the command “Windows” – house-servants would leap to the task and throw wide the windows allowing the stench of lower life forms to escape. When all else failed, the favoured method of correction was the high-velocity application of ancient plimsoll to young buttocks. Some trouser seats were more familiar than others with this ritual and there must have been some that remained unslippered for the duration of their school careers but for most of us the day would come when we too would have to submit to this indignity.

It was in the corridor outside the library where my own appointment with doom took place. I cannot recall the offence, (I hope it was insolence) but I do recall the impact being rather less than overwhelming and being richly compensated by the sight of my assailant’s facial distortion as he called on the dwindling resources of an ageing body to inflict the maximum concussion on his chosen target. The veins in the forehead duly swelled and throbbed, suggesting a coronary event may not be too far in the future. Thus I consoled myself.

The bad things always take precedence and there were some better things in addition to making common cause with like-minded dissidents. I’ve not forgotten the fragrant and fastidious C R Thomas, outfitted on the Boul’ Mich’, bestowing ingenious Gallic appellations on the great unwashed. A faint whiff of camembert, garlic and existentialism hung in the air as he rattled off his aphorisms in rapid-fire perfect French to almost universal incomprehension. A rare spirit, to be cherished unlike his dullard of a brother, F W, who bored for England. I was christened M. Barbe-Bleu ( a serial killer in embryo) while my comrade-in-arms, Chris Mullen became Marcel Moulle, le Gardien du Guichet – a subtle nod to Chris’s wicket-keeping prowess. Best of all, the class malcontent, the mutinous Rodney Pope, was renamed Mon Petit Arrosoir which translated as my little watering-can. The word arrosoir remains firmly lodged in my modest French vocabulary, to the exclusion of many thousands of others that would be far more useful.

The Art department was positioned on the farthest fringe of the school site to contain any contaminating influence. An excessive interest in art and design aroused grave suspicion on the part of the staff but the really good thing was that its existence was ignored leaving it free to serve as a safe haven for dissidents and deviants unwelcome anywhere else. A graduate of the Slade and a gentleman of almost imperturbable affability, F R Smith (known to all as Smut) was in charge of this ghost ship and presided over an oasis of tolerance. His air of uncomplicated human decency and amiable absent-mindedness was a blessed relief from the endless nagging, nit-picking exercise of unearned authority encountered everywhere else. Of course, as ungrateful adolescents we took full advantage of this good will as a licence to misbehave. The story has been told of an exchange of missiles between Smut and myself when the stick of chalk that he lobbed in my direction (as a gentle reminder to pay attention) was caught and returned in a spectacular feat of hand and eye coordination never repeated in my lifetime. In terms of heroism, modesty dictates a rider. Had this happened with any other of Dame Fuller’s Sturmbahnfuhrers I would have been lashed to a cycle rack, facing a firing squad composed of eager volunteers from the Kadet Korps – “Through the head, Sir, through the head”, I can hear them now, “No, through the testes, stop the bastard reproducing himself, Sir”. But the mild mannered Smut was an altogether different prospect – with an air of infinite sadness he felt compelled to put me in detention. For once, I had no complaint.

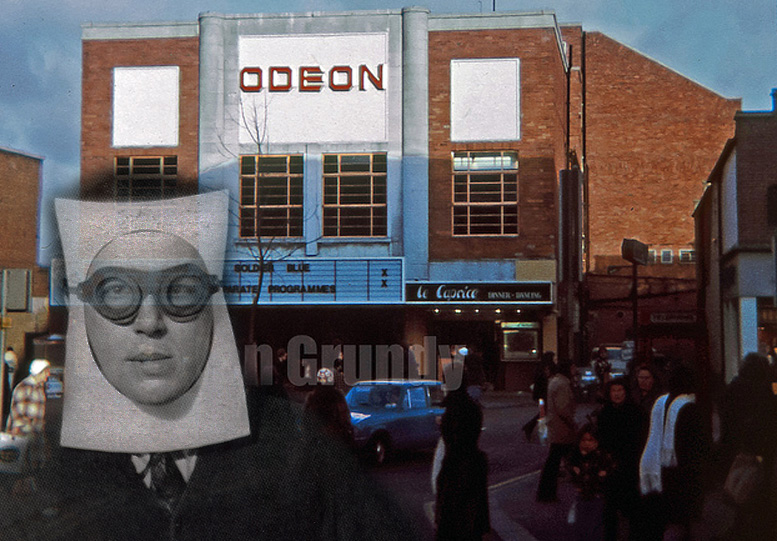

The great masters of surrealist painting, Magritte, Max Ernst and Dali were still around at this time and they had no more devoted admirers than Chris and myself, intoxicated with the universe of visual deviance conjured up in Paris almost four decades earlier. If André Breton had been onstage at the Watford Odeon reading from Les Champs Magnétiques Chris and I would have been in the front row, eyes shining with rapture. I raced through the A level syllabus in a single year, cheerfully absorbing huge dollops of history of art and architecture (to get me through the written papers) and tirelessly perfecting the art of hyper-realist drawing. By this method I secured an early release from the Cassiobury penal colony and advanced to the Foundation Course at the local art college, the proud possessor of a single A level. I’m even prouder of the fact that Mr. Gove would regard it as an utterly useless non-qualification.

When, to my eternal discomfort, I was a teacher myself I enjoyed affronting the dimmer of my colleagues (more than a few of them) with the thought that if I had to design an institution guaranteed to promote human cruelty and anti-social behaviour the ideal environment would be a place where the entire population would be required to march through endless narrow corridors from room to room at forty minute intervals and be nagged to distraction about the length or brevity of their skirts or hair, or their cosmetic preferences or body piercings. A place where the first duty of the staff is the defence of the uniform policy. I should have realised, considering the depth of my loathing of the arbitrary and indiscriminate sadism that infected WBGS, that life as a school teacher was really not for me. But instead, I flattered myself that having experience of some of the very worst that school could offer would enable me to offer something better to a new generation. What folly, what vanity!